|

Finite Geometry Notes

|

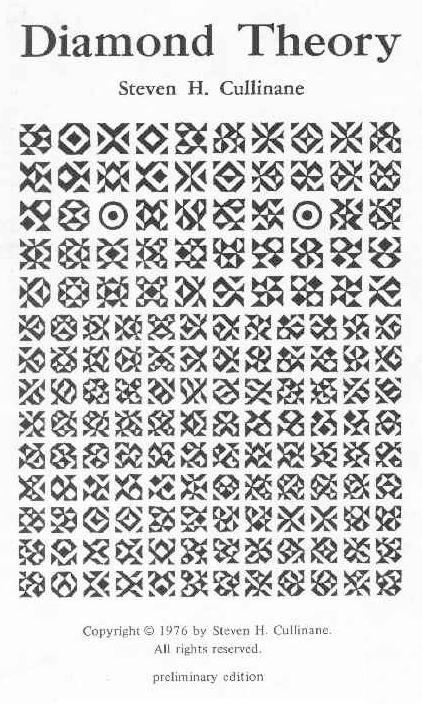

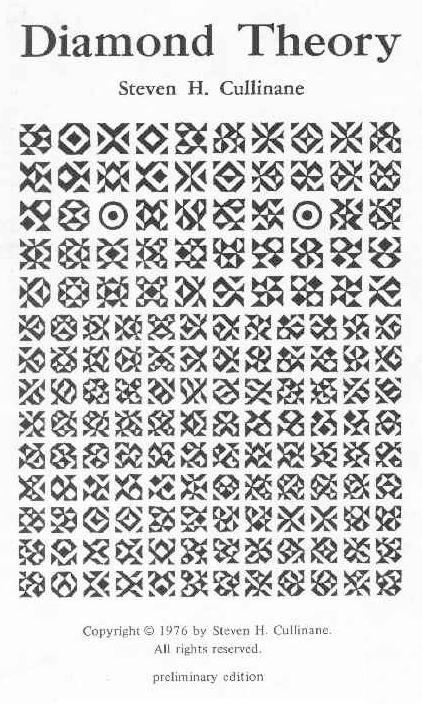

The image at right below shows the cover of a booklet I wrote in 1976. This booklet details the implications of what I call the "diamond theorem," after the diamond figure in Plato's Meno dialogue. For the technical details of the diamond theorem, see my website Diamond Theory.

The site you are now viewing, Math16.com, offers a less formal treatment of philosophical and literary matters related to the diamond theorem.

The following quotation describes, and inspired, the picture on the Diamond Theory cover:

"Adorned with cryptic stones and sliding shines,

An immaculate personage in nothingness,

With the whole spirit sparkling in its cloth,

Generations of the imagination piled

In the manner of its stitchings, of its thread,

In the weaving round the wonder of its need,

And the first flowers upon it, an alphabet

By which to spell out holy doom and end,

A bee for the remembering of happiness."

-- Wallace Stevens, "The Owl in the Sarcophagus"

Another description of this picture may be found in the novel A Wind in the Door. A main character in this book is the (singular) cherubim named Proginoskes. A comment from the author:

"Thank you for the diamond theory. It does, indeed, look more like Proginoskes than any of the pictures on the book jackets."

-- Madeleine L'Engle, letter of November 28, 1976

A

Mathematician's Aesthetics

The

Diamond Archetype

Aesthetics of

Parallelism

Geometry of the

I Ching

The

Non-Euclidean Revolution.

This book by Richard J. Trudeau, with a brief introduction

by H. S. M. Coxeter, traces in the recent history of

geometry the conflict between what Trudeau calls the

"Diamond Theory of truth" and the "Story Theory of truth"

-- known to more traditional philosophers as "realism" and

"nominalism."

Plato's

Diamond Revisited

Ivars Peterson's Nov. 27, 2000 column "Square of the

Hypotenuse" which discusses the diamond figure as used by

Pythagoras (perhaps) and Plato. Other references to the use

of Plato's diamond in the proof of the Pythagorean

theorem:

Meaning and the

Problem of Universals

A highly rated site on Logic and Ontology in the Google Web

Directory.

"You will all

know that in the Middle Ages there were supposed to be

various classes of angels.... these hierarchized celsitudes

are but the last traces in a less philosophical age of the

ideas which Plato taught his disciples existed in the

spiritual world."

-- Charles Williams, page 31, Chapter Two, "The Eidola and

the Angeli," in The Place of the Lion (1933),

reprinted in 1991 by Eerdmans Publishing

For Williams's discussion of Divine Universals (i.e., angels), see Chapter Eight of The Place of the Lion.

"People have

always longed for truths about the world -- not logical

truths, for all their utility; or even probable truths,

without which daily life would be impossible; but

informative, certain truths, the only 'truths' strictly

worthy of the name. Such truths I will call 'diamonds';

they are highly desirable but hard to find....The happy

metaphor is Morris Kline's in Mathematics in Western

Culture (Oxford, 1953), p. 430."

-- Richard J. Trudeau, The Non-Euclidean Revolution,

Birkhauser Boston, 1987, pages 114 and 117

"A new

epistemology is emerging to replace the Diamond Theory of

truth. I will call it the 'Story Theory' of truth: There

are no diamonds. People make up stories about what they

experience. Stories that catch on are called 'true.' The

Story Theory of truth is itself a story that is catching

on. It is being told and retold, with increasing frequency,

by thinkers of many stripes.... My own viewpoint is the

Story Theory.... I concluded long ago that each enterprise

contains only stories (which the scientists call 'models of

reality'). I had started by hunting diamonds; I did find

dazzlingly beautiful jewels, but always of human

manufacture."

-- Richard J. Trudeau, The Non-Euclidean Revolution,

Birkhauser Boston, 1987, pages 256 and 259

Trudeau's

confusion seems to stem from the nominalism of W. V. Quine,

which in turn stems from Quine's appalling ignorance of the

nature of geometry. Quine thinks that the geometry of

Euclid dealt with "an emphatically empirical subject

matter" -- "surfaces, curves, and points in real space."

Quine says that Euclidean geometry lost "its old status of

mathematics with a subject matter" when Einstein

established that space itself, as defined by the paths of

light, is non-Euclidean. Having totally misunderstood the

nature of the subject, Quine concludes that after Einstein,

geometry has become "uninterpreted mathematics," which is

"devoid not only of empirical content but of all question

of truth and falsity." (From Stimulus to Science,

Harvard University Press, 1995, page 55)

-- S. H. Cullinane, December 12, 2000

The correct statement of the relation between geometry and the physical universe is as follows:

"The contrast

between pure and applied mathematics stands out most

clearly, perhaps, in geometry. There is the science of pure

geometry, in which there are many geometries: projective

geometry, Euclidean geometry, non-Euclidean geometry, and

so forth. Each of these geometries is a model, a

pattern of ideas, and is to be judged by the interest and

beauty of its particular pattern. It is a map or

picture, the joint product of many hands, a partial

and imperfect copy (yet exact so far as it extends) of a

section of mathematical reality. But the point which is

important to us now is this, that there is one thing at any

rate of which pure geometries are not pictures, and

that is the spatio-temporal reality of the physical world.

It is obvious, surely, that they cannot be, since

earthquakes and eclipses are not mathematical

concepts."

-- G. H. Hardy, section 23, A Mathematician's

Apology, Cambridge University Press, 1940

"It's a thing

that nonmathematicians don't realize. Mathematics is

actually an aesthetic subject almost entirely."

-- John H. Conway, quoted on page 165, Notices of the

American Mathematical Society, February 2001.

"There are almost

as many different constructions of M24 as there

have been mathematicians interested in that most

remarkable of all finite groups."

-- John H. Conway in Sphere Packings, Lattices, and

Groups, third edition, Springer-Verlag, 1999

"The

miraculous enters.... When we investigate these

problems, some fantastic things happen.... At one point

while working on this book we even considered adopting a

special abbreviation for 'It is a remarkable fact that,'

since this phrase seemed to occur so often. But in fact we

have tried to avoid such phrases and to maintain a

scholarly decorum of language."

-- John H. Conway and N. J. A. Sloane, Sphere

Packings..., preface to first edition (1988)

Many actions of

the Mathieu group M24 may best be understood by

splitting the 24-element set on which it acts into a "trio"

of three interchangeable 8-element sets -- "octads," as in

the "Miracle Octad Generator" of R. T. Curtis. (See

chapters 10 and 11 of the above book by Conway and Sloane.)

It is a remarkable fact that the characteristics of such a

trio are not wholly unlike those of the more famous

structure described below by Saint Bonaventure.

-- S. H. Cullinane, March 1, 2001

"Beware lest you believe that you can comprehend the Incomprehensible, for there are six characteristics (of the Trinity) which will lead the eye of the mind to dumbstruck admiration. Thus, there is

"Was there really

a cherubim waiting at the star-watching rock...?

Was he real?

What is real?"

-- Madeleine L'Engle, A Wind in the Door, Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 1973, conclusion of Chapter Three, "The

Man in the Night"

"Oh,

Euclid, I suppose."

-- Madeleine L'Engle, A Wrinkle in Time, Farrar,

Straus and Giroux, 1962, conclusion of Chapter Five, "The

Tesseract"

For more on

philosophy and Quine, and also theology and angels, see

Is

Nothing Sacred? and Midsummer

Eve's Dream.

For a small memorial to Quine, see On

Linguistic Creation.

View notes (including the above on philosophy and Quine, etc.) from Author's Personal Journal

"It is a good

light, then, for those

That know the ultimate Plato,

Tranquillizing with this jewel

The torments of confusion."

- Wallace Stevens,

Collected Poetry and Prose, page 21,

The Library of America, 1997